TW: depiction sexual assault and light blasphemy

DISCLAIMER: I don’t think I’m better than you because I’m an atheist, I don’t think I’m any smarter either. I’m glad you have something that gives you purpose and guides you in life, it’s just not for me.

When I was younger, I imagined God as Grumpy from Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

Though my parents never pushed religion on me, it was all around me. I grew up in Türkiye, a secular country with a Muslim-majority population. I was raised alongside people who practiced Islam as well as those who didn’t. My grandmother is Christian; we’d celebrate Christmas together and exchange presents. I’d kiss my elders’ knuckles in exchange for money and candy, occasionally befriending a lamb before having kuzu pirzola for dinner. My childhood was a melting pot of beliefs, and I picked and chose at what I liked, ignoring the rest.

While on paper my country is secular, religion has made its way into several of our legislations in the past 25 years. One example is Türkiye’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention in 2021, claiming the convention had been “hijacked” by LGBTQ+ activists and went against our country’s “religious” morals and family values. Another example is the inclusion of religious affiliation on official government IDs until 2016 and the existence of an active ministry of religious affairs that constantly criticizes progressive laws.

A more recent example is the arrest of Turkish pop group Manifest during an 18+ concert for allegedly going against “morality” and being “obscene.” The real reason they were arrested wasn’t the corsets they were wearing but the crowd chanting “Hak. Hukuk. Adalet” (Rights. Law. Justice)—a chant we use to protest the current regime and the illegal detainment of Istanbul’s mayor and head of the main opposition party, Ekrem İmamoğlu. This weaponization of religion in the Turkish government has always been present and is worsening by the day.

Religion was everywhere around me. There was no escaping it, and it inevitably shaped some of my beliefs despite not being raised to be religious.

At ten years old, I moved away from my country. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t part of the majority. Everything I did was foreign. My classmates would ask if I needed a chaperone to speak to male peers, and my lack of a “bedsheet” (their term for a hijab or niqab) was heavily scrutinized. I was constantly treated differently for being Muslim, despite not necessarily identifying with the label.

As the only Turkish student in my school, I tried to befriend the few Muslim people around, assuming we’d connect automatically due to cultural similarities. Unfortunately, I wasn’t “Muslim enough”—I had never prayed in my life, nor was I a hijabi. My only Muslim trait was my aversion to pork. I decided to study Islam more closely to fit in. When that didn’t work, I turned to the Bible, and when that failed, I studied paganism. I felt the need to believe in something to belong. My parents assured me it was fine not to believe in anything, but I wanted to believe. I just wasn’t convinced God was real. I was treating religion like a trend, a tool to blend in with my peers.

I asked my father if he believed in God—if there was a man in the sky who dictated the universe. Instead of answering directly, he taught me that while religion could unite people and provide a moral code, it had mainly been used throughout history as a tool for subjugation. When I asked my mother the same question, she explained that religion began with agriculture in the form of animism and progressed into polytheistic then monotheistic religions. She told me she believed in nature—that if God existed, he wasn’t a man in the sky but the sun giving life to crops, the wind blowing through our hair, and a child’s laughter. When I asked what happened when we died, she said we simply disappeared, like going to sleep forever.

I liked that idea, but the permanence of death terrified ten-year-old me. I decided to believe in reincarnation; the idea that life and death were part of an unending cycle felt comforting and somewhat logical. But then, worries that I wouldn’t remember this life in the next one, that I wouldn’t have the same parents, sister, and friends, kept me up at night. I’d crawl into bed with my parents and cry for hours about how much I’d miss them in my next life. They promised they’d be my parents in every lifetime.

We had many conversations about religion. Some things they said comforted me, while others created a pit in my stomach. I started questioning why there was so much evil and suffering in the world if God was ever-loving. Every religious person I asked—whether following Abrahamic, Buddhist, or Pagan religions—told me that suffering was part of life, that we wouldn’t know happiness without suffering, that it was all about balance.

Even now, I agree with this notion to an extent. A world without suffering would be the same as a world without happiness: we would all be numb. However, I don’t believe the balance argument is realistic. Will the child whose entire family was massacred by IOF soldiers ever feel joy proportional to the suffering and injustice he’s faced? Will the woman who was raped or the man brutalized by police?

At what point does suffering stop being godly and become excessive? The idealization of suffering appears in almost every belief system across the planet, specifically in the form of self-flagellation. Monks starve or mummify themselves to achieve enlightenment. Catholics and Shia Muslims whip themselves to show remorse for sinning or to commemorate saints and prophets. Why do we consider self-inflicted pain virtuous? Not everyone in these faiths participates in self-flagellation with many religious scholars now discouraging it, but I still find it to be an interesting phenomenon.

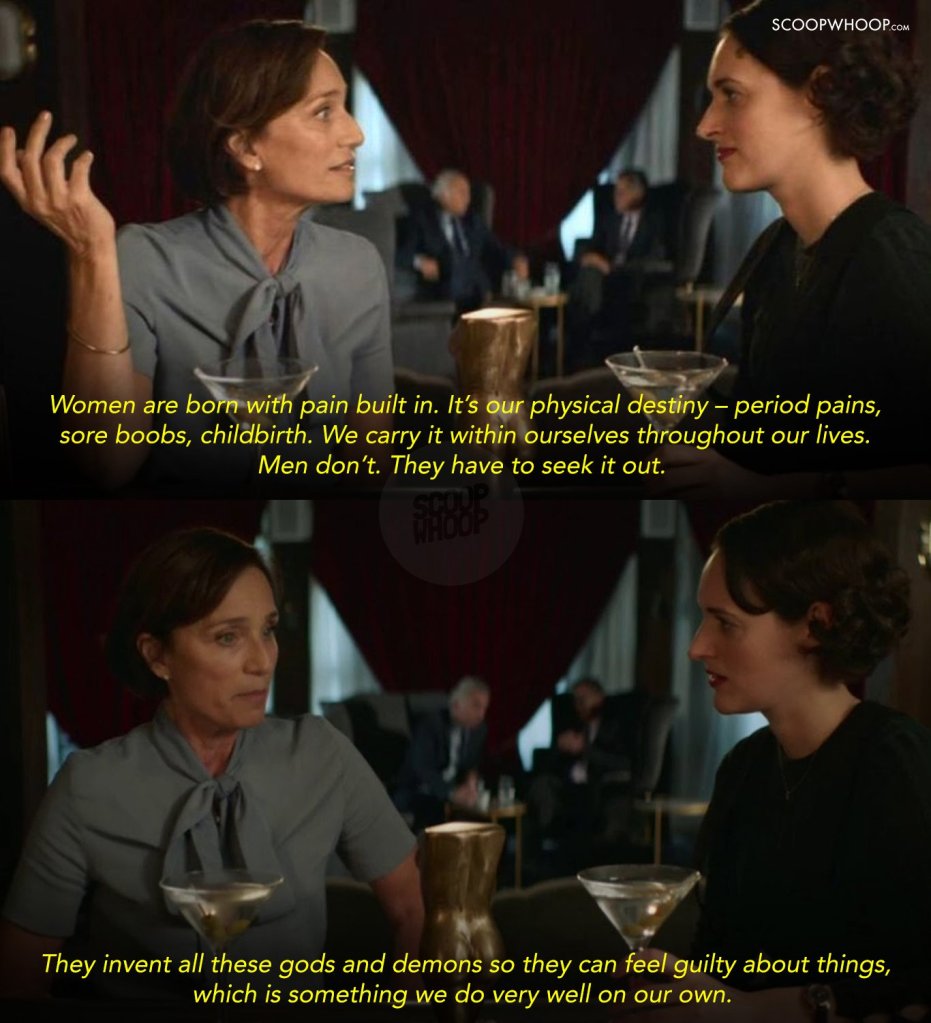

Even today, the belief that suffering is valuable or virtuous permeates our society. Art isn’t as valued when the artist hasn’t struggled in some way—through heartbreak, poverty, or war. It’s as if the artist’s pain gives the art value rather than the time, effort, and innovation that went into creating it. Similarly, we’re told that pain, specifically menstruation and childbirth, is God’s punishment for Eve eating the apple. Women who choose to give birth via C-section or with an epidural are looked down upon as having taken the “easy way out.” We’re constantly told that childbirth is supposed to be painful, that the pain is grounding and part of what makes giving life beautiful.

Even as a child, I found that strange and began researching the universe and the Big Bang. It was amazing how a series of events led to life on a floating rock, and learning about it excited me. Everything made sense, but I still wanted life to have meaning. Was I just born to do nothing? Did I simply exist without purpose? I wasn’t satisfied with that. I didn’t want the entire universe to be a series of coincidences. I was scared of what would happen after I died.

Then, two years ago, I was raped. I didn’t want to tell my parents, knowing that it would kill them. But I yearned for a parental figure’s reassurance, so I turned to Islam for comfort. I prayed every night, trying to understand why this happened to me. I wanted to feel God’s warm embrace and hear Him tell me everything would be alright. Instead, I felt like I was talking to myself, projecting my voice into an endless void alongside billions of others doing the same, hoping to be heard by a seemingly indifferent entity. I wondered what I could have possibly done to deserve this. I’m not a saint, and I’ll be the first to admit it, but I hadn’t done anything to deserve this kind of punishment from God—no one has.

I finally found my answer one night while cooking dinner: I hadn’t done anything wrong. God wasn’t testing me. I hadn’t angered Him simply by existing, because God isn’t real. I was trying to find logic in the illogical.

When I told one of my religious friends what happened to me, she said it was all part of God’s plan, that he was testing me, that I would be happier for it. Two years later, I can confidently say I’m not. I’ve become a shell of the person I used to be. I’m disgusted by men, I can’t stand being touched, and I’ve become so mean I barely recognize myself. It’s like I’m harboring a darkness that’s rotting me from the inside out. I want to peel off my skin and burn the world to ash.

Honestly, I think part of the reason I felt so alone is because I never truly believed in God. I thought I should, so I tried religion on like a costume, only to find it didn’t fit. I’m actively trying to heal now. I’ve read countless self-help books, I’m spending time with friends, and I’m going to the gym. I’m still scared of men, but it’s become somewhat manageable, and I’m working on being kinder. The rot is still there, but it has shrunk significantly. I don’t know if it’ll ever disappear, but I’m proud of the progress I’ve made. While life isn’t perfect right now, I’ve pulled myself out of a very dark place thanks to friends who have been nothing but supportive and patient. God may not be real, but my friends are, and I choose to believe in my connection with them instead of Grumpy the Dwarf.

© 2025 C. H. Gökdemir. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment